The unremitting human emancipation from nature –transformed into “culture”– is...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

Producing and marketing homes within demand-based pricing will continue to...

In Barcelona, a city which has, unfortunately, recovered its attraction...

Animac, scheduled for the 22nd to 25th of February in...

Would you like to walk around with the Giocconda under...

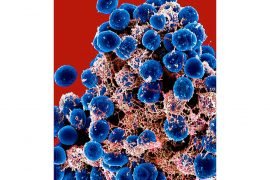

What happens when a person comes in contact with the...

The unremitting human emancipation from nature –transformed into “culture”– is...

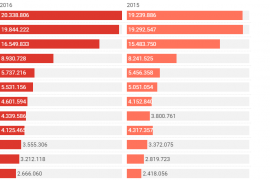

Barcelona, with 20.33 million overnight stays, led in 2016 the...

We are beginning to take in that it is possible...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

[dropcap letter=”D”]

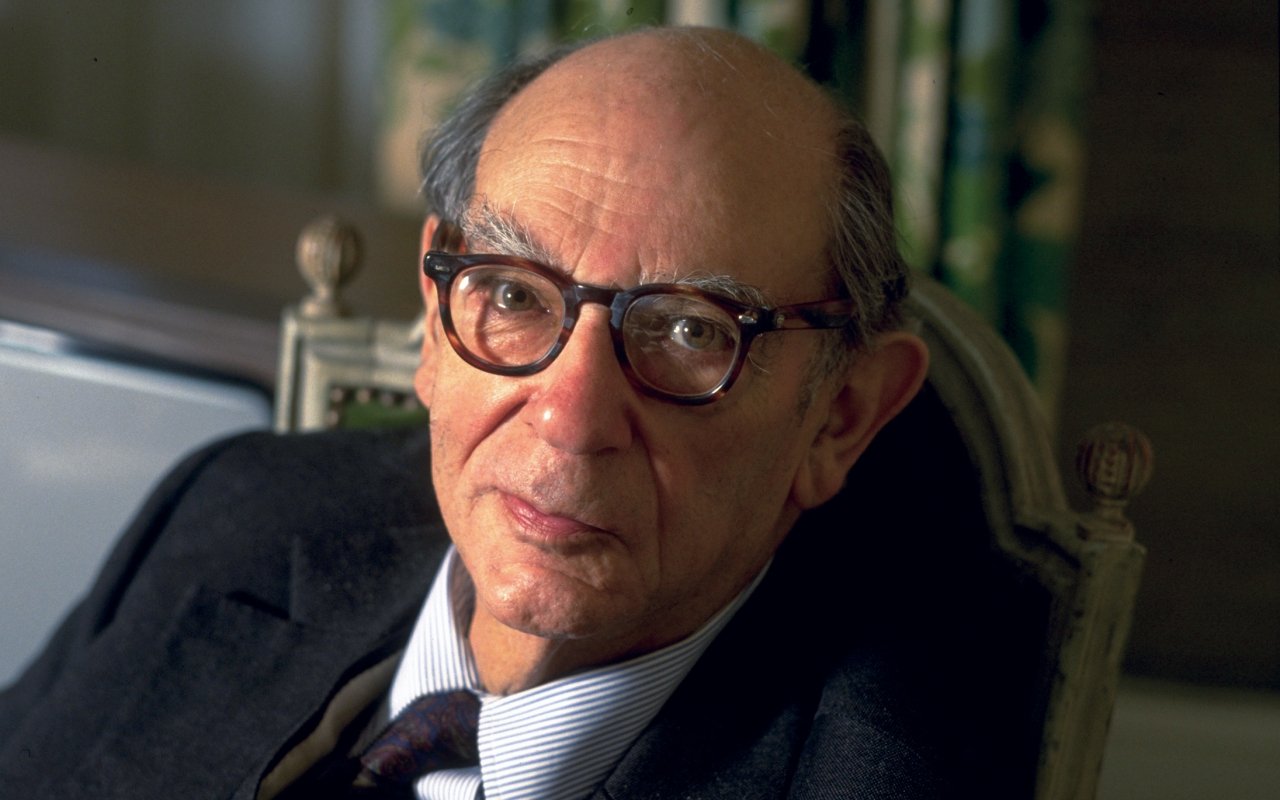

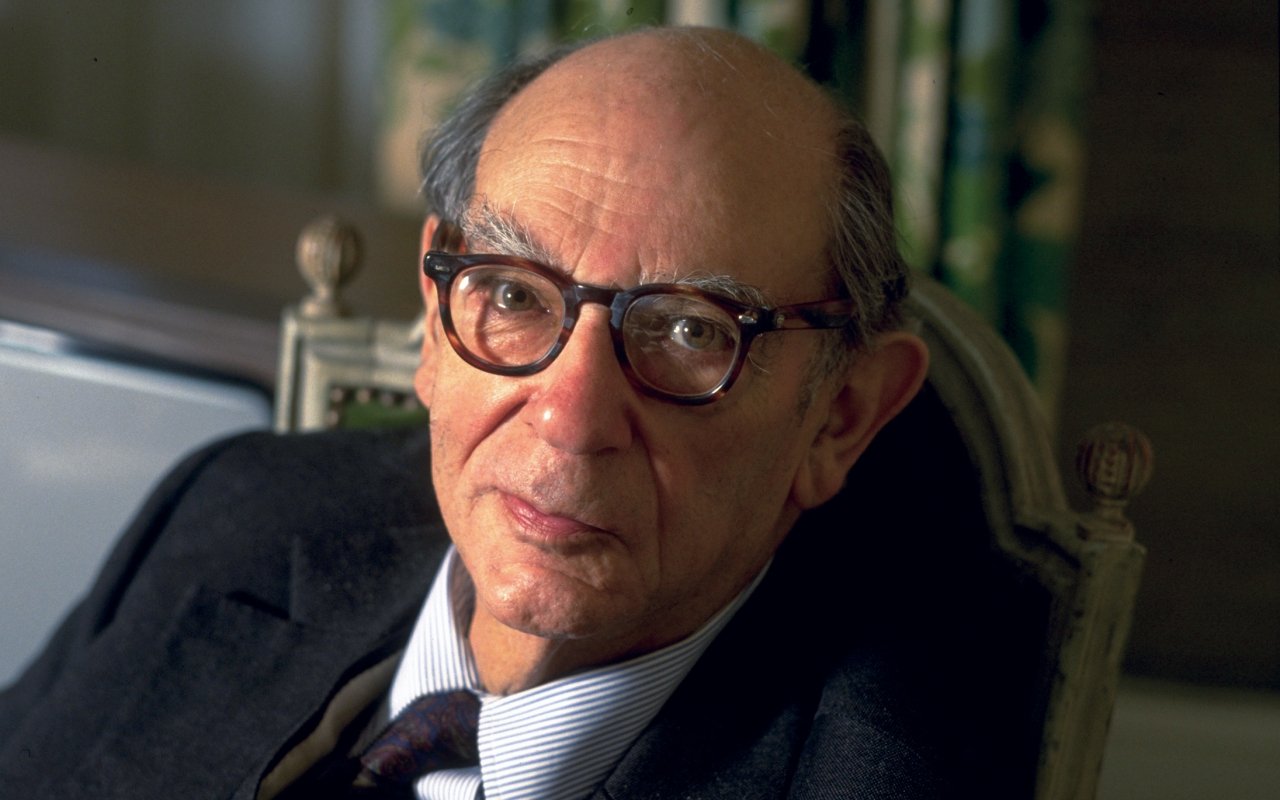

uring the Second World War, Winston Churchill had heard many good things about Isaiah Berlin. Later on, he would become one of the most eminent liberal thinkers of the 20th century. Berlin worked for the British intelligence in Washington. His reports were legendary. Churchill ordered that, as soon as Berlin arrived in London, he were invited for lunch in Downing Street. But someone confused him for the great songwriter Irving Berlin and when he went through London, he got invited at Number 10 Downing Street. Churchill asked him about his most recent decisive operation: “White Christmas”, replied Berlin —Irving—. Later on, Churchill commented on that: “This man’s speech is by far not as good as his writing”.

The compilation of those reports such as Washington Dispatches does not belong to the thinking corpus of Isaiah Berlin. This is rather closest to journalism that Berlin would experience. His was a collaboration in the British campaign for the United States to abandon neutrality and wage war. In there, we find his denial of historic inevitability. This impersonal interpretation of historical change gives the ultimate responsibility of what happens to entities or superpersonal, transpersonal forces, whose evolution is considered unprecedented in human history. This was, after all, the Third Reich that would last for a thousand years.

The American opinion was favourable to the allies but 80% of them were opposed to waging war, until the attack on Pearl Harbour. He arrived in New York, sent by the Ministry of Information in 1941. The following year, he was transferred to the Foreign Office. Until 1946 he was at the Washington Embassy. His reports, deeply appreciated by Churchill, are an insightful, detailed and synthesized description of the contemporary American society. He crosses the gateway to access the unclear present, loaded with current news, sometimes too real. Berlin is constantly lurking, as a journalist, chasing after the most significant data, the most relevant circumstance in such diverse organisations as syndicates, black associations or Jewish institutions. He narrates strikes and racial conflicts. Among his acquaintances, the great columnist Joe Alsop, the theologist Reinhold Niebuhr. He keeps track of isolationist press.

In 1980, in the prologue to his book Personal impressions Isaiah Berlin highlights the fact that, for his generation –young people in the 1930s— in Europe, with a political climate dominated by Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Salazar, and several dictators in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, Chamberlain’s and Daladier’s politics offered no hope whatsoever, and the only ray of light was coming from Roosevelt’s New Deal

One could say that the collection of articles Washington Dispatches (1981) has an anecdotal value as regards Berlin’s thinking, but it illustrates his relationship with political reality, and accumulated politics eventually becomes history. He manages to integrate confidential information, analyses of great columnists such as Walter Lippmann or the sinister Drew Pearson, technical administration reports, constant contact with high-ranking civil servants and, in general, whoever was somebody in Washington offices. The criteria are radically undetermined, as he focuses on the influence of human beings, their strategies and errors. The collection contains very much everything, especially from the day at the end of 1941 in which Washington waged war against Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbour. Churchill visits Washington, MacArthur resists in the Philippines, President Roosevelt gives his “chat by the chimney”. Battle of the Coral Sea, advanced in the war industry, Stalin asking for a Second Front, De Gaulle is confirmed, Madame Chiang Kai-Shek speaking in the Capitol, and so on and so forth until Roosevelt’s death and Truman entering the White House. Not a humble endeavour. In 1980, in the prologue to his book Personal impressions Isaiah Berlin highlights the fact that, for his generation –young people in the 1930s— in Europe, with a political climate dominated by Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Salazar, and several dictators in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, Chamberlain’s and Daladier’s politics offered no hope whatsoever, and the only ray of light was coming from Roosevelt’s New Deal.

In his diaries —1942-2000—, historian Arthur Schlesinger, one of his best American friends, explains how Berlin congratulated him for a survey published in Times Literary Supplement in which he said that Hannah Arendt was one of the most overrated writers of the century. Years later, Schlesinger gathered Arendt and Berlin. The meeting was a total disaster. To Berlin, Hannah Arendt was too solemn, striking, Teutonic and Hegelian. She believed that Berlin’s genius was too frivolous. Berlin did not believe that History had a fixed pattern and that a planned Paradise ended up being hellish. The biggest risks are optimism and fatalism: History advanced linearly towards achievable perfection or inevitable evil. Two determinisms.

[dropcap letter=”D”]

uring the Second World War, Winston Churchill had heard many good things about Isaiah Berlin. Later on, he would become one of the most eminent liberal thinkers of the 20th century. Berlin worked for the British intelligence in Washington. His reports were legendary. Churchill ordered that, as soon as Berlin arrived in London, he were invited for lunch in Downing Street. But someone confused him for the great songwriter Irving Berlin and when he went through London, he got invited at Number 10 Downing Street. Churchill asked him about his most recent decisive operation: “White Christmas”, replied Berlin —Irving—. Later on, Churchill commented on that: “This man’s speech is by far not as good as his writing”.

The compilation of those reports such as Washington Dispatches does not belong to the thinking corpus of Isaiah Berlin. This is rather closest to journalism that Berlin would experience. His was a collaboration in the British campaign for the United States to abandon neutrality and wage war. In there, we find his denial of historic inevitability. This impersonal interpretation of historical change gives the ultimate responsibility of what happens to entities or superpersonal, transpersonal forces, whose evolution is considered unprecedented in human history. This was, after all, the Third Reich that would last for a thousand years.

The American opinion was favourable to the allies but 80% of them were opposed to waging war, until the attack on Pearl Harbour. He arrived in New York, sent by the Ministry of Information in 1941. The following year, he was transferred to the Foreign Office. Until 1946 he was at the Washington Embassy. His reports, deeply appreciated by Churchill, are an insightful, detailed and synthesized description of the contemporary American society. He crosses the gateway to access the unclear present, loaded with current news, sometimes too real. Berlin is constantly lurking, as a journalist, chasing after the most significant data, the most relevant circumstance in such diverse organisations as syndicates, black associations or Jewish institutions. He narrates strikes and racial conflicts. Among his acquaintances, the great columnist Joe Alsop, the theologist Reinhold Niebuhr. He keeps track of isolationist press.

In 1980, in the prologue to his book Personal impressions Isaiah Berlin highlights the fact that, for his generation –young people in the 1930s— in Europe, with a political climate dominated by Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Salazar, and several dictators in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, Chamberlain’s and Daladier’s politics offered no hope whatsoever, and the only ray of light was coming from Roosevelt’s New Deal

One could say that the collection of articles Washington Dispatches (1981) has an anecdotal value as regards Berlin’s thinking, but it illustrates his relationship with political reality, and accumulated politics eventually becomes history. He manages to integrate confidential information, analyses of great columnists such as Walter Lippmann or the sinister Drew Pearson, technical administration reports, constant contact with high-ranking civil servants and, in general, whoever was somebody in Washington offices. The criteria are radically undetermined, as he focuses on the influence of human beings, their strategies and errors. The collection contains very much everything, especially from the day at the end of 1941 in which Washington waged war against Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbour. Churchill visits Washington, MacArthur resists in the Philippines, President Roosevelt gives his “chat by the chimney”. Battle of the Coral Sea, advanced in the war industry, Stalin asking for a Second Front, De Gaulle is confirmed, Madame Chiang Kai-Shek speaking in the Capitol, and so on and so forth until Roosevelt’s death and Truman entering the White House. Not a humble endeavour. In 1980, in the prologue to his book Personal impressions Isaiah Berlin highlights the fact that, for his generation –young people in the 1930s— in Europe, with a political climate dominated by Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Salazar, and several dictators in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, Chamberlain’s and Daladier’s politics offered no hope whatsoever, and the only ray of light was coming from Roosevelt’s New Deal.

In his diaries —1942-2000—, historian Arthur Schlesinger, one of his best American friends, explains how Berlin congratulated him for a survey published in Times Literary Supplement in which he said that Hannah Arendt was one of the most overrated writers of the century. Years later, Schlesinger gathered Arendt and Berlin. The meeting was a total disaster. To Berlin, Hannah Arendt was too solemn, striking, Teutonic and Hegelian. She believed that Berlin’s genius was too frivolous. Berlin did not believe that History had a fixed pattern and that a planned Paradise ended up being hellish. The biggest risks are optimism and fatalism: History advanced linearly towards achievable perfection or inevitable evil. Two determinisms.