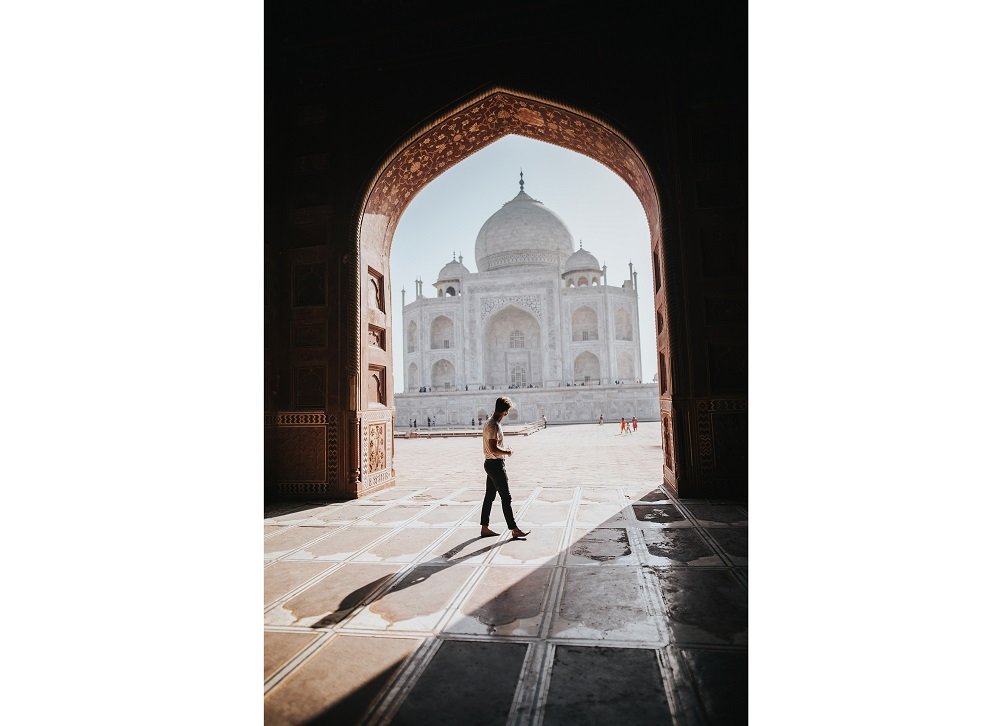

Taj Mahal, the eternal mausoleum of a dead princess, resembles a living body thanks to inlay stones encrusted in marble. Today, a gorgeous sunny day, all of them were shining bright, beautiful jades and turquoises from China, Lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, coral from Baghdad, and malachite from Siberia! Its polished shiny-white marble throbs as if proclaiming the resurrection of Princess Mumtaz Mahal, “the chosen one”. It is as if love emanated from death, the eternal light within the pale fluorescent whiteness.

Irresistibly wonderful Taj Mahal, “the Crown of Palaces”! There is always a time for all perfect masterpieces, like this pantheon, to become deified. These artworks contain such wisdom, such unfathomable and huge geometrics, such grace; they are so suitably rounded in their completeness that they are reminiscent of Divinity itself. Certainly, Taj Mahal represents Divinity on account of its transparency, its metaphysical breathing and its supernatural halo.

“As far as we know –writes Goethe somewhere in his great travel chronicle Italian Journey–, classic artists, like Homer, had considerable knowledge and understanding of nature as one could possibly imagine (…) Such as the great creations of nature, the very same ones that men’s idea of natural laws originated. All arbitrary and presumptuous things collapse and only the necessary ones and God remain”.

Taj Mahal is pure living matter, an organic architectural artwork (like Gaudí’s). This is like so because it has been built following the laws of nature itself. But by human hands and minds. If those creators were next to us, we would listen to their words in awe. We hardly remember their names but we surely admire them for their facts. All those artists, thousands of artists, brought out the Taj Mahal. Gaudí also brought the dragon out of him, symbolically speaking. All his collaborators, all the artists supporting him, brought the dragon out of themselves.

But nowadays, at this stage in human history, it can be sadly stated that the artistic techniques are no longer applied artwork: the techniques –isolated from artistic hands– have lost spirituality. And it’s as if the ancient bond between the will’s drive and the tactile sensitiveness is irretrievably lost.

Before the Taj Mahal –lying on the ground, level with the red-bursting cinnamons– one compelling truth imposes itself, and this is the Goethean theory of the Urphänomen (the “original phenomenon”): “everything that is factual is a theory in itself. There is no need to look into such phenomena: they are a theory on their own”. Therefore, watching them implicitly means thinking them.

According to this belief, Goethe insists that, before a specific phenomenon, one must put on hold all thinking, all judgement, and allow this to take place intuitively rather than rationally, a sensorial apprehension of the sense of a specific reality. And this reality is both one and whole, as Heraclitus defended over 2,500 years before.

Taj Mahal is the proof of the unfathomable. What does its structure contain that it reminds us of a nave enclosed by four spacerocket-looking minarets? Looking down from its carefully drafted gardens, squirrels scamper around –looking nervous about having lost their paradise–, the thick-billed parrots come in and out of the tree trunks with holes from woodworm, and the marigolds and the strange bell-shaped deep-blue flowers.

We, the visitors from afar, embody the mystery, here. They look at you, they touch you as if you came from another world: the world of lush matter. We represent the presence of the Unknown just like the extraordinary levitation of stone could be to us. But since this is no standard two-way road, we feel that the Taj Mahal also belongs to us totally, because we no longer ask ourselves how much it is worth but rather what it means to us.

At midday in the Indian city of Agra, by the river Yamuna, we surrender to the pleasure of watching the tiny square-shaped stars, of contemplating the fragile and stagnant art that some invisible children linger over… We hear we can only fly kites now during springtime. In summer, the heat from the sun is so intense that you cannot look up in the sky.

Then, we look up and watch the flying kites. In the same sky, turtledoves do their ritual flight, and when they stop, we can hear their drowning and keen cooing.

Back to Delhi from the Jelam Express –who knows how far it comes from!– the journey back takes four hours, twice as much as the outward journey. Thus, we slept all the way surrounded by plastic curtains separating the different train compartments.

When the light goes down, the sky is dyed indigo blue. Until, drowsy due to the train rattling, a clear-sighted dream suddenly assails me: we find ourselves amidst human depths in a dimly lit Indian station. “They don’t know where they’re going! They don’t know where they’re going!” We can hear voices shouting from behind us. But we walk on, determined, and confident that the way is up the stairs, to the other side of the track. The rags call on us as if they were our own shroud. From the top of the metal bridge, I see a lamp stand shining a dim light.