Rents increase 9% due to competitive pressure and reach 3,000...

Hollywood has taught that three possible destinations await humanity: fighting,...

"Mirrors, inside and outside of reality" is one of the...

In Barcelona there are four or five people who spread...

The successful Mobile World Congress held recently in Barcelona has...

In a few years on the market, Tesla has established...

Pregnancy immerses the expectant woman in a sea of joys...

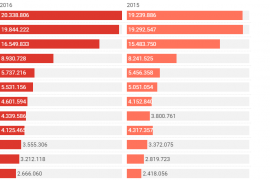

Barcelona, with 20.33 million overnight stays, led in 2016 the...

The most popular use of supercomputation in industry is the...

A good friend is with you to the end of...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

[dropcap letter=”Y”]

et another year, the Russian pianist Grigory Sokolov has summoned crowds of faithful fans to the Palau de la Música Catalana, virtually filling the large hall. This makes eleven seasons in a row. It hardly matters that the definitive programme – that is, the pieces he will actually perform (with the usual but relatively predictable careen between the Baroque of Bach and Rameau and the mature, balanced Romanticism of Brahms) – is only advertised just a few weeks prior to the concert. So, just as with the best concerts, the respectable fans go for the performer, whom one could consider from a romantic perspective as a decanter of essences or an alchemist. And yet, these descriptors fit the strange case of Sokolov only loosely, if at all.

By default, bearing in mind the recurring success of his performances, one is tempted to think that behind this mass phenomenon (within the world of classical music, of course, which is tiny compared to pop fandom) there may be a huge marketing effort. A company that curates his image and invests in communication, in cahoots with the principal involved – the artist being promoted – who is sold as a genius, a divo onstage and a charmer off. So here’s another disappointment: Sokolov is not a technical prodigy, nor does he ooze likeability at public events, which, by the way, are few and far between, except for in concerts. His persona and his ways suggest an artist from another era or, perhaps more aptly, from no particular era.

His persona and ways suggest an artist from another era or, perhaps more aptly, from no particular era

Sokolov is a musician who primarily delights himself – yes, himself – with the pleasure of performance without so much as a glance into the mirror of tradition. There is no trace of historicist criteria in the way he plays. And just as when he appears onstage he immediately sits at the piano bench, hardly looking at (or, therefore, acknowledging) the audience, his interpretation of the chosen pieces does not get mired in dialogues or inter-era nods, nor does he try to revive the lost essence of the score in a way that is supposedly closer to the composer’s true spirit. This becomes quite clear, without looking any further, in his three sonatas by Haydn in the first part of this year’s recital at the Palau. Nor does he re-create a kind of virtuosity as spectacular as it is vacuous, the kind of circus performance that has sparked admiration in all eras, including ours, of course.

To the contrary, Sokolov prioritises the declamation of the phrase; he constructs a coherence that is not merely subjective – capricious, motivated by chance or by the circumstances of his personality. Nor does it result from objectification, the quest for the musical quintessence. Where his modus operandi is seen the most and best is in the second part of the series of Impromptus by Schubert. The flow of these false improvisations, with facile melodies and wholly smooth, powerful textures, allows the performer a time fluctuation, a voluntary alteration of the tempi and intensities, and with them a generous modulation of moods, which he dispenses at the piano with an unperturbed mien and no affectation whatsoever.

The flow of these false improvisations, with facile melodies and wholly smooth, powerful textures, allows the performer a time fluctuation

Ignasi Cambra, a talented young musician whom we shall soon spotlight in an audiovisual piece, who regularly attends Sokolov’s recitals – and he’s not the only musician to attend them – told us that some kind of activity can always be perceived in the pianist’s way of playing which is the outcome of a more profound plumbing of the score. It is a complete immersion, which makes his interpretation original and worth hearing. Sokolov resolves the most intricate passages with apparent ease, but more importantly he enjoys making most of the nuances audible in terms of the relationship between the notes and their actual sound. He seems to be testing the piano, amplifying the beautiful vibration it produces. This may be why he is not satisfied with just playing the programme but almost always offers a series of encores.

The third part of the programme, which isn’t really a secret at this point – despite the fact that it is never announced in advance – tends, indeed, to be made up of a juicy string of encores, where the pleasure of performing is reencountered, up-close. Generally speaking, it is a series of brief pieces (he comes back onstage around ten times, amidst bows and extra pieces) in which he alternates the danzabile elegance of a Rameau, a harpsichord composer whose piano versions require precise fingering, with the magnificent palette of colours and affects characterising the oeuvre of Chopin, one of the composers invoked the most often in this third act of the programme. Sokolov bows to the audience’s demands, but with an enigmatic indifference.

The fandom and admiration that some young performers profess for him leads us to understand that he – a rare specimen in our day – may precisely become a touchstone

He doesn’t appear to be cold out of arrogance, vanity or disdain. It’s as if he reserved all his communicative nuances, any form of complicity, for his musical performances. This is not the only or the least fascinating of the paradoxes posed by his personality as an artist, because the fandom and admiration that some young performers profess for him leads us to understand that he – a rare specimen in our day – may precisely become a touchstone for the future. Never before have so many musicians boasted such outstanding technical training. Exceptional performance, however, is more difficult to teach. In this sense, there is no doubt that his effort to read the works from within is also worth noticing.

The counter-discourse that Sokolov embodies – without striving to indoctrinate, of course, which would be alien to his personality – not only appears genuine but is also successful: it is moving, and therefore it attracts many listeners to the concert halls. Perhaps the best proof that music transcends mere entertainment comes from artists themselves, those who – like Grigory Sokolov – experience it onstage with a particular intensity, rendering the emanation of this inexplicable magnetism possible. Their origins unknowable, he provides aesthetic experiences that earn much greater loyalty than other promises of immediate bliss.

[dropcap letter=”Y”]

et another year, the Russian pianist Grigory Sokolov has summoned crowds of faithful fans to the Palau de la Música Catalana, virtually filling the large hall. This makes eleven seasons in a row. It hardly matters that the definitive programme – that is, the pieces he will actually perform (with the usual but relatively predictable careen between the Baroque of Bach and Rameau and the mature, balanced Romanticism of Brahms) – is only advertised just a few weeks prior to the concert. So, just as with the best concerts, the respectable fans go for the performer, whom one could consider from a romantic perspective as a decanter of essences or an alchemist. And yet, these descriptors fit the strange case of Sokolov only loosely, if at all.

By default, bearing in mind the recurring success of his performances, one is tempted to think that behind this mass phenomenon (within the world of classical music, of course, which is tiny compared to pop fandom) there may be a huge marketing effort. A company that curates his image and invests in communication, in cahoots with the principal involved – the artist being promoted – who is sold as a genius, a divo onstage and a charmer off. So here’s another disappointment: Sokolov is not a technical prodigy, nor does he ooze likeability at public events, which, by the way, are few and far between, except for in concerts. His persona and his ways suggest an artist from another era or, perhaps more aptly, from no particular era.

His persona and ways suggest an artist from another era or, perhaps more aptly, from no particular era

Sokolov is a musician who primarily delights himself – yes, himself – with the pleasure of performance without so much as a glance into the mirror of tradition. There is no trace of historicist criteria in the way he plays. And just as when he appears onstage he immediately sits at the piano bench, hardly looking at (or, therefore, acknowledging) the audience, his interpretation of the chosen pieces does not get mired in dialogues or inter-era nods, nor does he try to revive the lost essence of the score in a way that is supposedly closer to the composer’s true spirit. This becomes quite clear, without looking any further, in his three sonatas by Haydn in the first part of this year’s recital at the Palau. Nor does he re-create a kind of virtuosity as spectacular as it is vacuous, the kind of circus performance that has sparked admiration in all eras, including ours, of course.

To the contrary, Sokolov prioritises the declamation of the phrase; he constructs a coherence that is not merely subjective – capricious, motivated by chance or by the circumstances of his personality. Nor does it result from objectification, the quest for the musical quintessence. Where his modus operandi is seen the most and best is in the second part of the series of Impromptus by Schubert. The flow of these false improvisations, with facile melodies and wholly smooth, powerful textures, allows the performer a time fluctuation, a voluntary alteration of the tempi and intensities, and with them a generous modulation of moods, which he dispenses at the piano with an unperturbed mien and no affectation whatsoever.

The flow of these false improvisations, with facile melodies and wholly smooth, powerful textures, allows the performer a time fluctuation

Ignasi Cambra, a talented young musician whom we shall soon spotlight in an audiovisual piece, who regularly attends Sokolov’s recitals – and he’s not the only musician to attend them – told us that some kind of activity can always be perceived in the pianist’s way of playing which is the outcome of a more profound plumbing of the score. It is a complete immersion, which makes his interpretation original and worth hearing. Sokolov resolves the most intricate passages with apparent ease, but more importantly he enjoys making most of the nuances audible in terms of the relationship between the notes and their actual sound. He seems to be testing the piano, amplifying the beautiful vibration it produces. This may be why he is not satisfied with just playing the programme but almost always offers a series of encores.

The third part of the programme, which isn’t really a secret at this point – despite the fact that it is never announced in advance – tends, indeed, to be made up of a juicy string of encores, where the pleasure of performing is reencountered, up-close. Generally speaking, it is a series of brief pieces (he comes back onstage around ten times, amidst bows and extra pieces) in which he alternates the danzabile elegance of a Rameau, a harpsichord composer whose piano versions require precise fingering, with the magnificent palette of colours and affects characterising the oeuvre of Chopin, one of the composers invoked the most often in this third act of the programme. Sokolov bows to the audience’s demands, but with an enigmatic indifference.

The fandom and admiration that some young performers profess for him leads us to understand that he – a rare specimen in our day – may precisely become a touchstone

He doesn’t appear to be cold out of arrogance, vanity or disdain. It’s as if he reserved all his communicative nuances, any form of complicity, for his musical performances. This is not the only or the least fascinating of the paradoxes posed by his personality as an artist, because the fandom and admiration that some young performers profess for him leads us to understand that he – a rare specimen in our day – may precisely become a touchstone for the future. Never before have so many musicians boasted such outstanding technical training. Exceptional performance, however, is more difficult to teach. In this sense, there is no doubt that his effort to read the works from within is also worth noticing.

The counter-discourse that Sokolov embodies – without striving to indoctrinate, of course, which would be alien to his personality – not only appears genuine but is also successful: it is moving, and therefore it attracts many listeners to the concert halls. Perhaps the best proof that music transcends mere entertainment comes from artists themselves, those who – like Grigory Sokolov – experience it onstage with a particular intensity, rendering the emanation of this inexplicable magnetism possible. Their origins unknowable, he provides aesthetic experiences that earn much greater loyalty than other promises of immediate bliss.