[dropcap letter=”T”]

wo weeks ago, Enric Juliana wrote in La Vanguardia that the title of the brief pamphlet by Jordi Amat La confabulación de los irresponsables [The Conspiracy of the Irresponsible] describes the time —from an optimistic view, this time encompasses the last five years— of the Kafkian Der Prozess [Catalan process] that we have had to endure, especially in Barcelona. In the hope that this insight is not seen as criticism to this article, I will allow myself to disagree with it and here are the reasons.

From the moment that the first mass demonstrations took place in Passeig de Gràcia back in 2012 and, as the secessionist proposal was consolidating and veering into a disconnection process from the Spanish State —that eventually did not happen—, journalists, essayists and columnists have used the diary Abans del sis d’octubre [Before the 6th of October], published in 2008, by lawyer Amadeu Hurtado to back up their arguments, usually against Catalan independence.

The diary, unpublished until then, did not mark an era, obviously, nor did it have any impact on its contemporaries. Instead, other texts, now completely forgotten, did have an influence. This is the case of Crítica del 6 d’octubre [Criticism of the 6th of October] by propagandist Jaume Miravitlles (1935), a text written to exempt the Catalan President Companys from the failed ‘Hechos de octubre de 1934’ [Incidents of October 1934] and blame the then Counsellor of the Interior, Josep Dencàs, and the independentist faction he led within the Catalan Republican Party (ERC), Catalan State.

Hurtado’s diary, on the other hand, has made an impact on current essayists. This may be so because there is still, among writers, the desire to make their view last and survive, in the style of the documentary by journalist John Reed, Ten Days that Shook the World (1919) on the Russian October Revolution. Transcending, rather than analysing or explaining, is the main aim of his work.

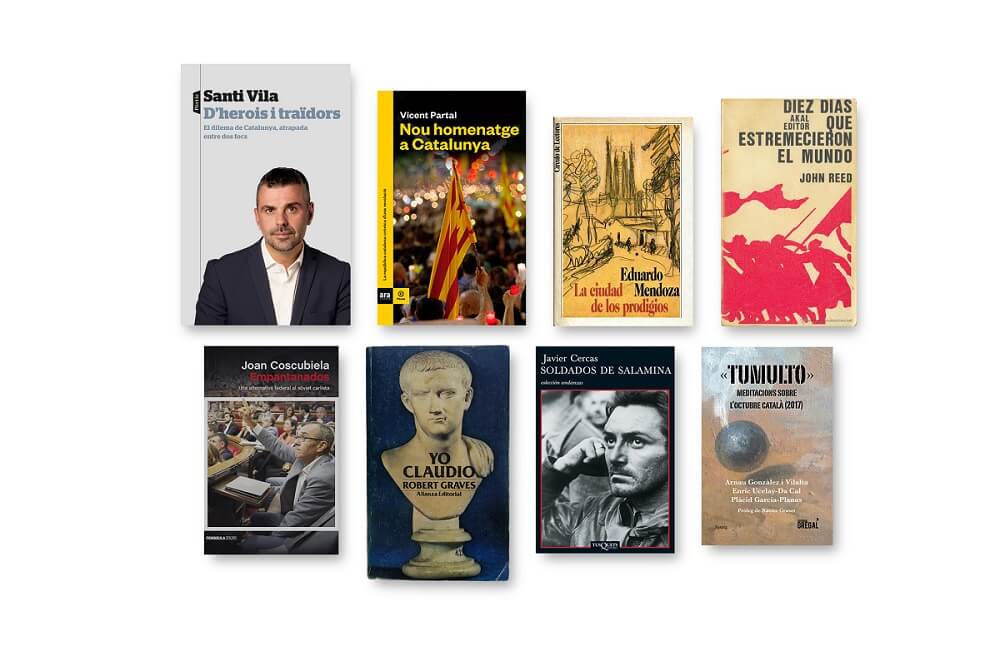

About the Catalan case, for example, somewhere in between Reed and Hurtado’s self-confessed contemporary shift could we rank Tumulto [Turmoil] by historians Enric Ucelay-Da Cal and Arnau Gonzàlez Vilalta, and journalist Plàcid Garcia-Planas crossing urgent notes on their insights and viewpoints into the Catalan October incidents. Undoubtedly, future researchers will leaf through it to gauge the pulse of other outlooks and views. Although this book will probably fall short of Abans del sis… as its author, a Republican lawyer had an active role in the incidents, while the authors of the latter were mere observers with an opinion of their own. Admittedly, that’s no little feat but not good enough for such mission. The most Hurtadoish-style to date are the testimonial books by Santi Vila De héroes y traidores [From Heroes to Traitors] or Joan Coscubiela Empantanats [Bogged down]. From a peripheral view on the other side of the Mississippi river, at the other end of the spectrum, that of the independentist agitprop, stands Vicent Partal’s Nou homenatge a Catalunya [New Homage to Catalonia].

Most certainly, these and many similar essays, be them more or less accurate in their analyses, are interesting and complement each other. We will probably have to read them all, or perhaps waiting for some synthetic work that can offer a fresh sweeping view on these recent events. Still, none of them will describe with pinpoint accuracy the days we lived dangerously. The future outlook on these incidents will not be tampered with by the extent to which the current media supporting them keep praising them. While reality had once been an important asset, worth delivering objectively, now this asset has been downsized. Not because reality, past or present, does not exist —this could be argued—, it is because reality does not matter anymore.

In the Catalan cultural sphere, this was so well before the appearance of the digital world and the liquid modernity. More and more, people reading historical novels imagine they are reading history. Absurdity has reached a point that readers prefer ‘the truth’ in Victus, Soldados de Salamina or I, Claudius to works by such historians as Joaquim Albareda, Joan Maria Thomas, Mary Beard or such contemporary authors as Hurtado and the like.

It will then be a talented soul capable of creating a novel like Vida privada [Private Life], Plaza del diamante [Diamond Square], Ciudad de los prodigios [City of Prodigies], Diario de un ladrón [Diary of a Thief] or, alternatively, a trilogy like Julià de Jodar’s, L’Atzar i les ombres [Fate and the Shadows], who will crystalize the view of the separatist process in the popular imagery. Like Fallada’s feat in the years of the Weimar Republic and the Hitlerian regime or Dickens in Victorian England, paradoxical as it may seem, what will capture the image of our revolutionary decade in Barcelona will not be an essay about reality, but fiction, plain and simple. After all, who cares about John Ferling’s analysis on the life of the second president of the United States, when a tv series like John Adams knocks it off in seven entertaining (yet biased) episodes?

Featured image

From top to bottom and from letf to right: D’herois i traïdors, Santi Vila / Nou homenatge a Catalunya, Vicent Partal / La ciudad de los prodigios, Eduardo Mendoza / Diez dias que estremecieron el mundo, John Reed / Empantanados, Joan Coscubiela / Yo Claudio, Robert Graves / Soldados de salamina, Javier Cercas / Tumulto, Arnau Gonzàlez i Vila, Enric Ucelay-Da Cal, Plàcid Garcia-Planas.